There is a crew of bikers hanging out in the churchyard that houses Europe’s, 'possibly the world’s ' oldest living thing. Can that be true? The faded information board doesn't seem sure.

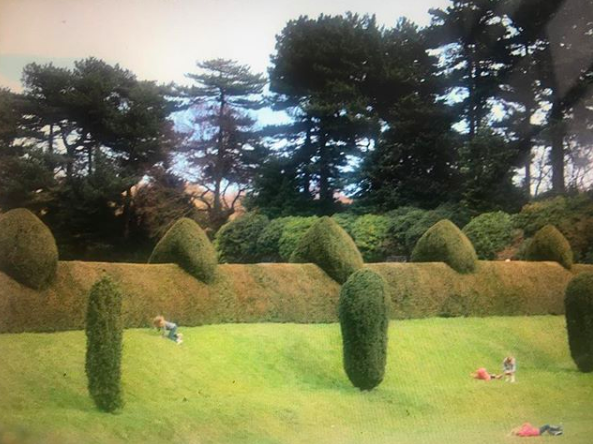

We slide past them to look at the yew, caged behind a stone wall to protect it from souvenir hunters who have left much of it missing, but its 5000 year old roots intact. The claims on the signage, with its graphics of the pyramids, Stonehenge and the birth of Jesus, all of which the yew outdates, seem incongruous next to its reality: it's gnarled and it's branches sprawl a bit chaotically, but it's not that gnarled, not that sprawling.

The bikers seem confused too. The Ewe bar next door to the tree is shut. The Ewe and the Yew as desolate as each other today. I was hoping for a wee birthday drink, one of them tells us. World's oldest man drinks world's oldest whisky next to world's oldest tree jokes another.

What else lives as long as trees? So maybe this is the world's oldest living thing, here in this churchyard, signposted Hotel and Yew. How can we possibly know? Who is counting? How long have we been counting for?

Immortality isn't part of nature, scientists don't think. Every organism does eventually die. But there are some beings which appear not to age

"appear not to', jokes the scientist, 'because to be honest we haven't studied any of them for 500 years. It's hard enough to get grants for five year projects"

When i turn 28 my dad tells me that from here on in I will find myself deteriorating. But I skip away unbothered by these portentous birthday wishes because at 28 i still feel immortal, still cycle home from parties drunk and half blind, glasses in my pocket, still run across roads milliseconds ahead of oncoming cars and

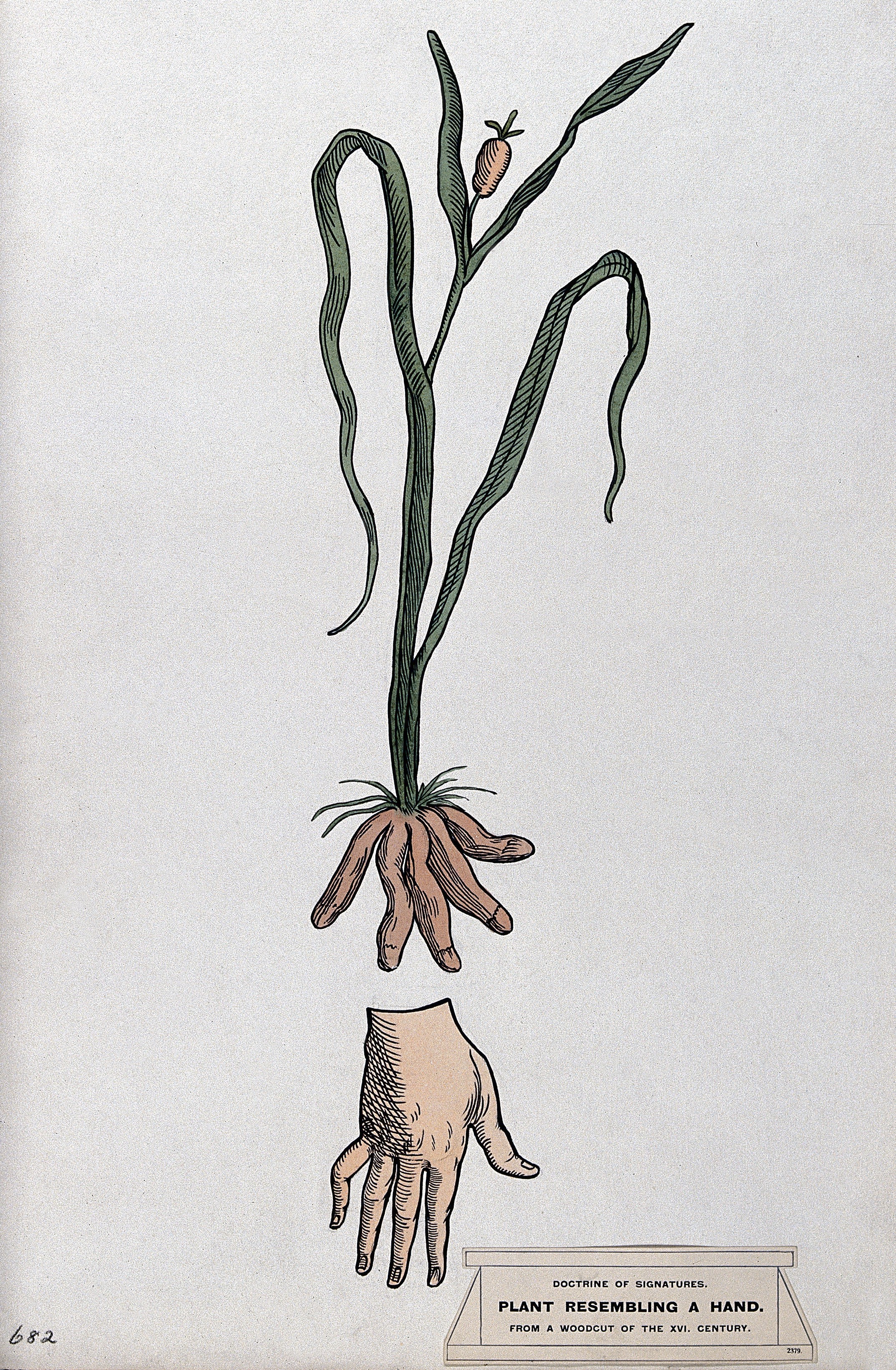

The Olm, for example. A cave dwelling salamander which 'does not undergo metamorphosis and instead retains larval features', The Olm is also known as the Human Fish, perhaps because of the resemblance of its pale skin to white skin, though the thing that strikes me when i google The Olm is its three fingered but otherwise human? arms and hands, that it looks something like a pallid worm with elbows.

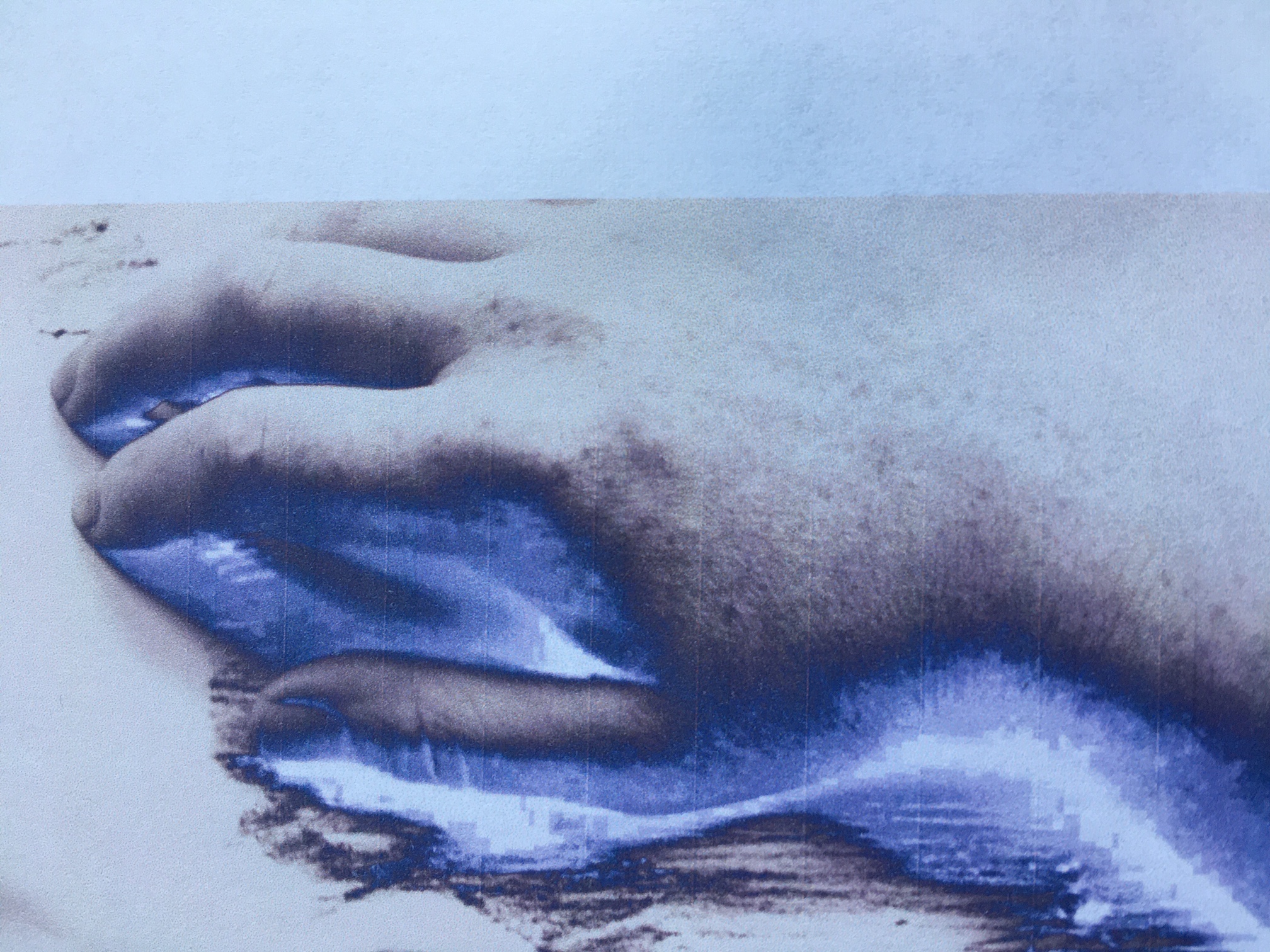

I show my hands to the table of friends gathered to see me on a rare night off from new parenthood. I pull at the skin on the back of my hands to show them how far i can stretch it now, 'I feel so old' I laugh, though what i mean is that I feel exhausted, and afraid of what has happened to me in this first year of motherhood.

First the fat was sucked from beneath my skin, as my boy fed on my milk. As a prize for my feat of procreation, my mother gave me the tiny engagement ring that my dad had given her before their brief marriage, and it fit my newly slim fingers. Then, maybe it was the exhaustion of 'sleepless nights' (how harmless that sounds), but a year in and the skin of my hands had become crepe-y, thousands of tiny lines to fold and ripple when i flexed my fingers.

Always exposed to the elements, your hands probably give away your age more than any other body part"

CARS ARE MADE OF PAINT’ he shouts one evening as he walks home from preschool with his mother.

He may know something of the world but he still lives on the surface for now, unaware that objects may have many layer. That underneath their candy shell, cars are dull and metallic and mechanical.

By his logic you and I are made of skin

;

A chatty middle aged man is gently rubbing my nose with gloved fingers. He presses slightly harder and hmms. The intimacy of the gesture is striking after 6 months of avoiding touch, and I find myself enjoying his careful, precise stroking, it’s similar, I think, to the way I used to stroke my cat’s nose, which always made her lean her head back in purring, dribbling bliss. He presses a cool, gelled up instrument to my skin, magnifying my pores to what I imagine is a grotesque gaping size. I am so close to his face that i can see lines of sweat between the creases of the folded frown lines on his brow and it's something i can't bear to look at, i can't bear to be this close to, so i close my eyes just as my cat would have done and wonder at how a small blemish on my surface might actually be something to fear.

In the cab home after the examination the taxi driver has taped a flimsy plastic screen between herself and the passenger seats. She asks me if I’m finishing work, and feeling my ability for small talk hampered by my cloth mask and my brush with mortality I tell her that I’ve been in hospital, an appointment that I’d been anxious about. I tell her that they thought I might have skin cancer, but I don’t, it's something else much less serious.

I'd googled my diagnosis whilst i waited for the cab. The diagnosis feels revelatory, and i read about it as though i am reading through a potted history of my life's embarrassing moments, the flush that for as long as I can remember has burned my face when i exercise, drink, get hot or cold, am embarrassed, stressed or tired is a tangible thing with support groups and a medical name. I'm will no longer be dismissed or patronised as a blusher, a careless pale person who has spent too long in the sun, a drunk.

Crack open a bottle of wine the cabbie suggests, and i say i probably will even though apparently that makes it worse.

She exhales into her own mask, and it's time to deliver her own unsolicited intimacy, as though she's been waiting to press play since i climbed into her cab. She’s got a very gentle voice, speaks slowly, and you notice that you’re straining to hear her.

'I’m picking up my son after you, driving down south. It'll be a long drive, and i suppose i'm dreading it really. We don’t get on at all. We’re very different. He got a girl pregnant, up here. And then he left, chasing another woman, and now he’s dropped her (or she’s dropped him) so I’m driving down to bring him home with me. I'm just not sure he's a good person, she says, and as a mother, that's so hard to realise.

The worst thing, love? she says, it’s his feet. I’ll be four hours in the car, with his feet, and the smell - my god, it’s as though they’re rotting. Sometimes, she says, as she pulls up in front of my house, sometimes I think that’s symbolic.

she says bye and good luck and I say bye and it’s only been a 10 minute journey how did we get into all that, and i get in the door and scrub my hands clean

When the boy was born his hands were crusted and wrinkled. He had long sharp nails that scratched his own face in the night and his mother's face as he fed from her.

But before long his hands took on the appearance of inflatables, little puff hands his parents would croon. Little puff hands to smash and prod and flail and figure out with. SMASH into porridge, SHHHH to run sand between your fingers, BANG plastic and metal thrown to the floor.

And later a packet of slime which comes free with a magazine. His mother mixes it with warm water and films his hands on her phone as they squelch through the bowl full of green. She has to blink away thoughts of the foetal hands in formadahyde jars that she would sometimes visit at the Hunterian museum when she was a student at UCL.

They've slimmed down now, 3 years on. He is dextrous and intentional with them, mostly. Manipulating tiny toy parts to his will, gently picking ladybirds from leaves, he fit them firmly into his mother's hands and tells her that he never wants to grow up.

After 3 years of material experiments the boy feels as though he knows something of the world.

A gardener friend tells me about the seeds trapped under the layers of city, and that on occasion a 2000 year old seed will germinate, breaking through a crack somewhere in the fabric of the city. fulfilling its historic green destiny. I think about the genetics that caused a

I was born in the dark and the wet, emerging between rocks from the flabby egg that held me separate from my mother. For the first months of my life i had no need of food and i swam the dark and the wet where i was born and where i remained, twisting my pale body to propel myself through it, twisting myself into fissures and cracks where i'd find others of my kind and we'd twist together cool and enveloped, the only bright spots in our endless night.

For a long time it is always dark. It is always wet. I am always long and white.

As his third year progresses the boy begins to think more about his interior. 'I am made of meat', he tells his parents. He worries briefly that he is made of the same kind of meat that he enjoys tucking into at dinner time, but then decides that ' my kind of meat tastes horrible'. His mother knows that he could only taste sweet and delicious but decides to keep this to herself.

THE ANCIENT GREEKS BELIEVED THAT RUMBLING TUMMIES WERE THE VOICES OF THE DEAD

Skin connection to emotion how touch in one place can induce shivery tingle dear. The dance of compassion in a world wtihout tough

She starts to see hands everywhere.

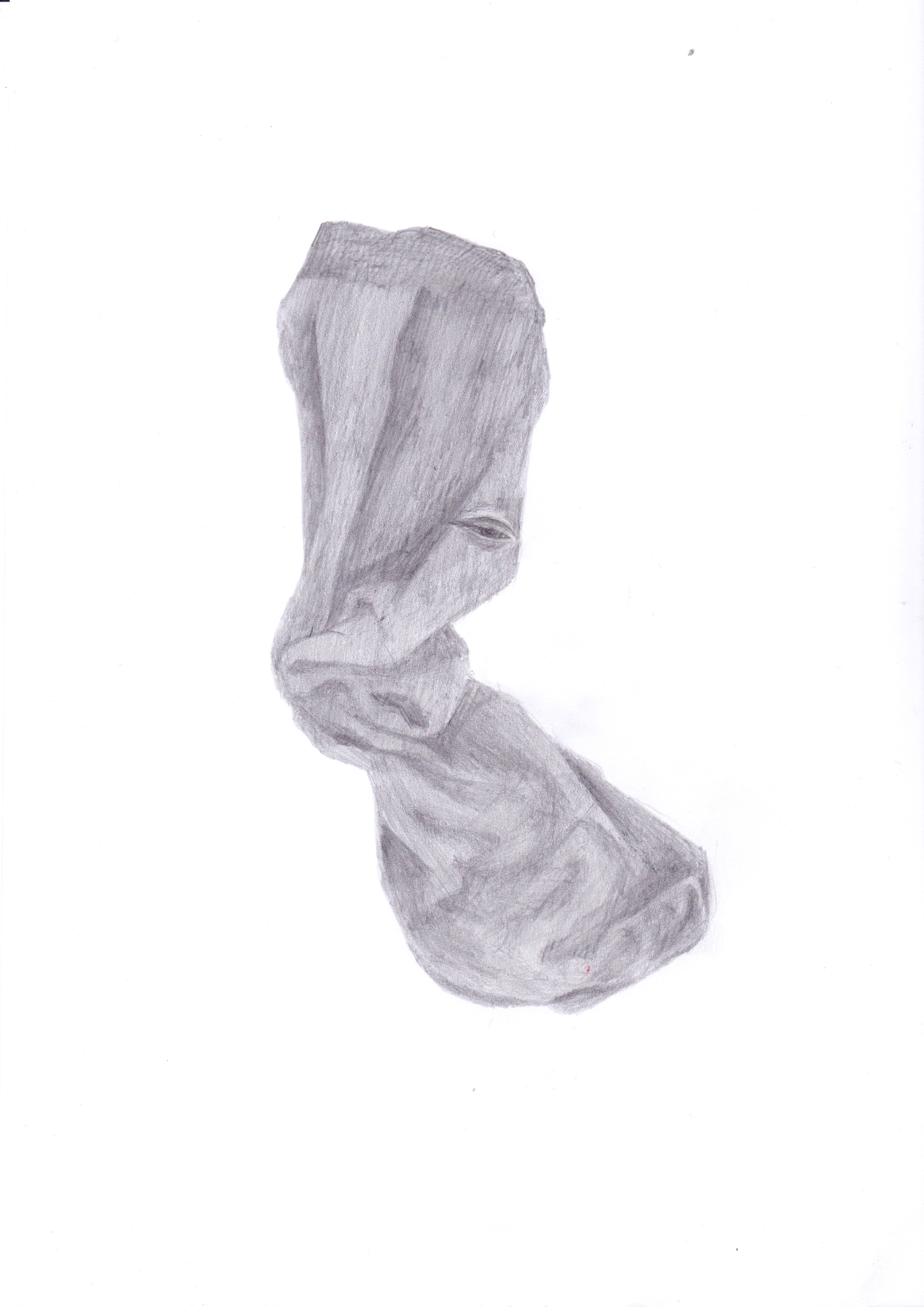

On Mondays, bin day, the streets fill up with rubbish. It blows into her front yard, and rattles down the street. Amongst the tissue, receipts and crisp packets that find their way onto her front step, a flurry of gloves. Blue and white plastic surgical gloves, builders gloves, gardening gloves and the occasional lost mitten. The seemingly endless rain of that winter ensures they become sodden enough to stay where they land until she gingerly removes them, conscious of the strangers hands which once filled them.

Each morning as she surveys the new arrivals, the gloves sign to her. One holds a discarded fag between index and middle finger. One swears. A thumbs up, a set of crossed fingers. She takes these signs as omens for how her day ahead will be, although the days at the moment have little to differentiate themselves from each other. The morning that a rain sodden surgical glove gives her the finger she returns indoors and

Coffee Morning, October 2020

6 desks in a room which is bright with autumn sunlight. On each desk is a roll of kitchen roll.

As five masked women enter the room, Jane, at the back of the room, offers tea and toast, which is heartily accepted by each woman.

They plop down with some relief into plastic chairs and peel off their masks, as Jane, who keeps her floral mask and surgical gloves on shuffles round bearing plastic cups (not the small white kind but the extra large red cups of American house parties in films) of tea, each cup made to the slightly differing requirements of one of the six. Next she carries a slice of buttered toast, slid onto a paper plate, to each desk.

Jane now sits down and peels off her surgical gloves, and removes her own mask. She comments on how sweaty her hands are which induces a little queasiness in some of the women, despite knowing that the sweat was safely contained whilst she was handling their tea and toast.

The mood in the room is sad but gregarious. The new restrictions are commented on with shaken heads and sighs, as is the weather which has turned again. The autumn sunlight has clicked off like a buib, and the room is now dark. Jane pops her mask on to shuffle over to the light switches, one of which has been taped off like the benches in the park, so that only one of the strip lights flicker on, spotlighting one of the desks whilst the rest remain in the gloom.

The woman in the spotlight, we’ll call her woman number one, has brought along a crochet project that’s she’s been working on for the past year, she tells the group. It was supposed to be a cape, she says, but she’s forgotten where she started, what pattern she’s working from and what size crochet hook she should be using. And she spilled tea on it one day. And here, here is where she fell asleep, crocheting in bed. Here’s a mistake from when she was watching something distressing on the telly and got distracted. It soothes the mind though she says. But maybe I’ll start over.

Woman number two speaks from her dark corner. She says that it sounds as though woman number one’s crochet project contains within it the story of all the moments that have passed as she’s been making it. That she shouldn’t start over. And what a time to remember, she says. The room murmurs its appreciation of this concept as well as in reassurance for woman number one.

The glow of a phone screen illuminates the desk where woman number three sits. She holds up the screen to the group who are each spaced at least 2 metres from her, so can’t clearly see what she’s showing them. She’s been redecorating her house she says. painted her hallway red, and stencilled a pattern of bamboo round the doorways. At least it was supposed to look like bamboo, she giggles, but it looks much more like bones.

Woman number two thinks for a moment then puts her mask on and comes out from behind her desk and advances a few paces towards woman number three’s desk, stopping far short of the desk, though, and planting her feet firmly on the carpet, before leaning her upper body forwards and squinting at the phone screen which woman number three holds out as far as her arm can reach. She steps back to her desk and sits down

Woman number four speaks for the first time as woman number two takes her mask off, and as the movement of the clouds allows a wedge of sunlight to slide across the room, a point of the wedge landing on her cheekbone. She tells the group how the masks distress her, how she feels claustrophobic and trapped by them, how they remind her of things that have happened to her that she doesn’t want to remember. The group understands immediately what she means.

Woman number five twists her body towards woman number 4 and leans forward, her face falling into the sliver of sunlight. She reaches her hand out as though to offer a comforting stroke or pat of the shoulder, although her hand falls far short of woman number 4. She says that she has noticed how quick people have become to judge, how little we seem to bee able to consider the truth that everyone has their own story, that sometimes people have to make their own rules for survival.

Woman number 4 reaches out a hand back to woman number five, and says that yes, it’s been hard to feel as thought she has to . Woman number one has started playing some music on her phone. The small sounds of swelling strings and an electronic beat kicks in before an emotive key change. Woman number one is tapping her fingers on her desk and woman number 2 starts swaying and singing along to the words, it’s a famous song. And then they are all swaying, and tapping, and humming for a moment as the song soars on the tinny phone.